By New York Times Editorial Board

In 2010, the Government Accountability Office found that nearly two-thirds of the 50 largest violators of federal wage and hour laws won new federal contracts for work ranging from food processing to cloud computing and that 20 of the 50 largest violators of workplace safety laws were also federal contractors.

Those findings were echoed in a report in 2013 by the Democratic staff of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. That report found that, from 2007-12, 49 major federal contractors were cited 1,776 times for substantial wage and safety violations and paid $196 million in penalties and assessments. Those same employers were awarded $81 billion in federal contracts in 2012 alone.

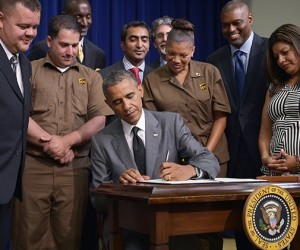

It would seem noncontroversial to advise federal procurement officials to steer clear of companies with repeated and egregious violations that cheat, sicken, harm, and kill workers. But when President Obama signed an executive order in late July to that effect, the pushback from industry was immediate, notably from the Associated Builders and Contractors, whose members do 60 percent of federal construction jobs, and from the International Franchise Association, whose members run concessions at federal venues.

Both organizations have denounced the order as a form of “blacklisting.” The building contractors have vowed to fight it the courts and in Congress.

Under existing law, federal officials can bar contracts to companies with serious labor law violations. Mr. Obama’s order helps to execute the law by requiring bidders for federal contracts to disclose their labor-law violations going back three years and by putting an official at each federal agency in charge of tracking the disclosures.

The administration has been careful not to burden contractors and certainly does not seek to penalize companies for isolated, inadvertent and easily correctable mistakes. If a company has not had any violations, it simply checks a box attesting to that fact. If a company reports violations, procurement officials are to look for evidence of pervasive, repeated, willful or serious wrongdoing in weighing whether to deny a contract.

In addition, the order does not take effect until 2016 — giving companies time to start cleaning up their labor records if necessary. Before then, the regulations and guidance required by the order are subject to public comment, giving companies time to register their concerns.

It would be outlandish for industry groups to argue that procurement officials and the public do not have the right to know about a contractor’s compliance with federal labor laws or defend practices that hurt workers.

The contractors who oppose the order seem to have forgotten that they are bidding for taxpayer dollars. They are not entitled to contracts; they must qualify. And when they obtain a contract, they are working for the people, not the other way around.

Original Editorial: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/20/opinion/the-right-to-cheat-and-maim.html?_r=0